History of Pashmina

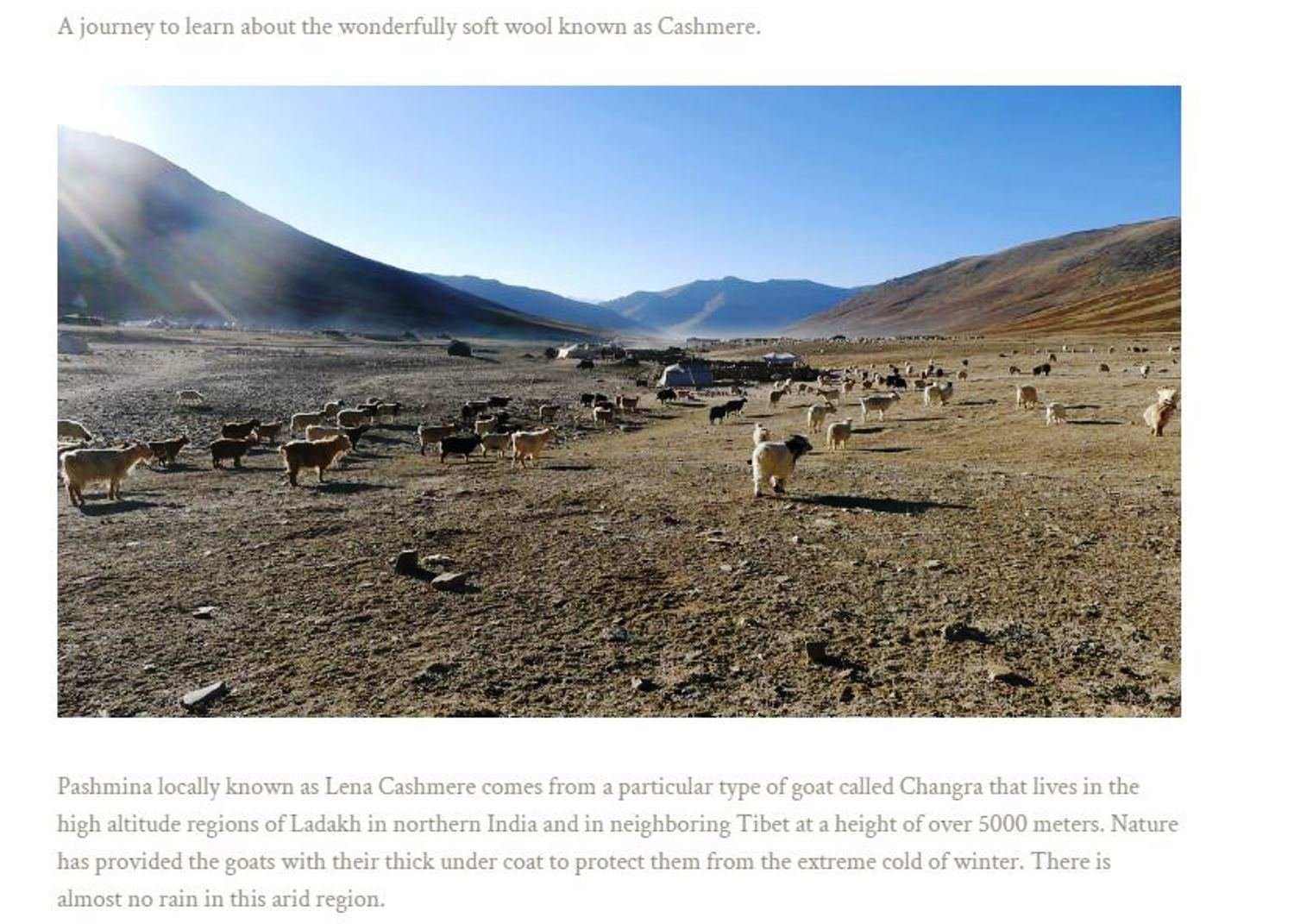

Pashmina goats are found in Himalayan mountains

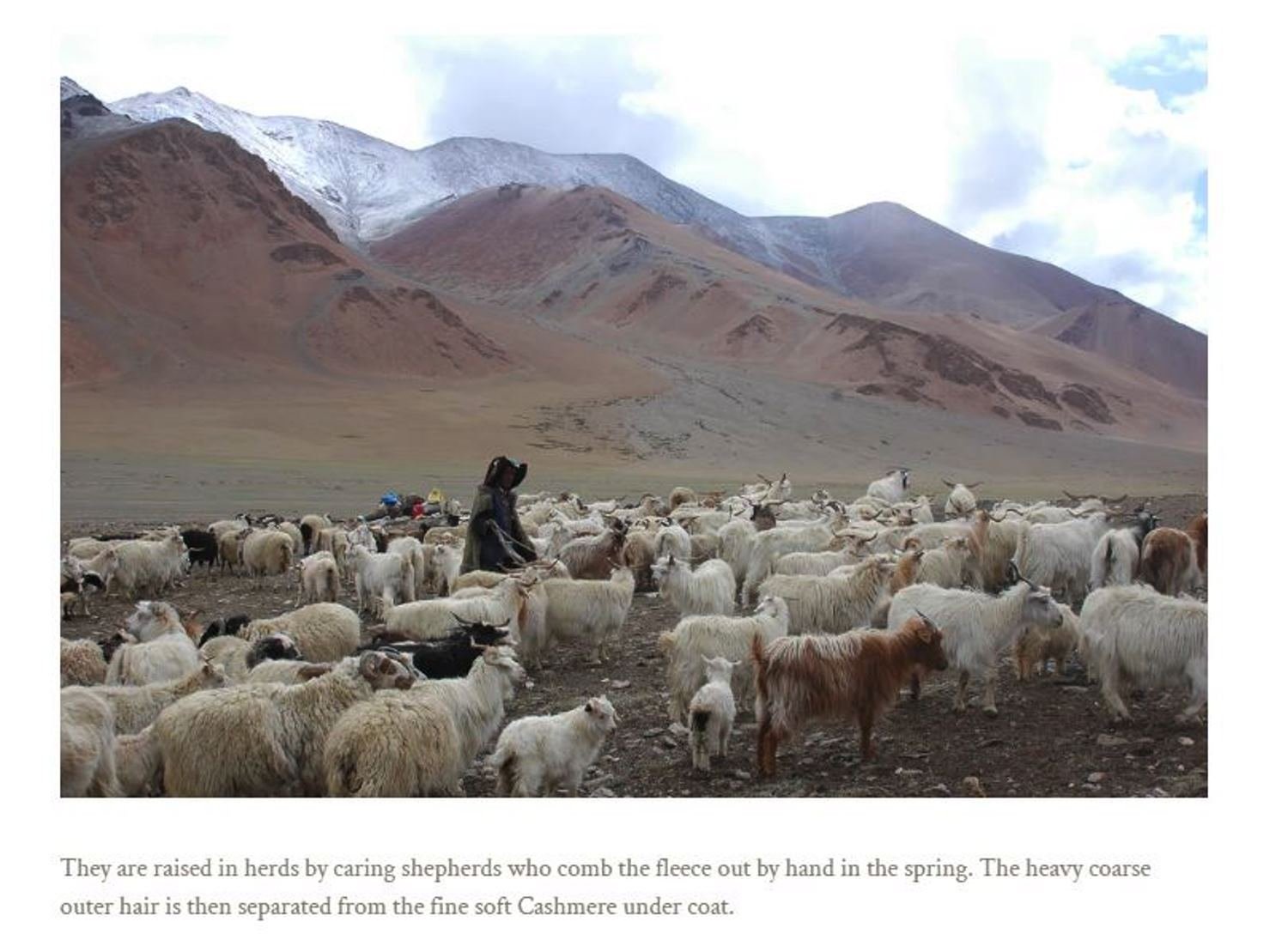

Nepal, a small landlocked country in southern Asia, is bordered by Chinese Tibet to the north and India to the east, south, and west. Despite being one of the least developed nations, Nepal is renowned for its stunning Himalayan mountain range, which includes the world's highest peak, Mount Everest. The country's economy is primarily based on agriculture and forestry, with a long history of producing traditional hand-woven carpets and textiles. Recently, the focus has shifted to pashmina and cashmere shawls, made from the exceptionally fine wool of the Himalayan mountain goat, the Chyangra.

The pashmina wool is extracted from the goat's downy undercoat, with the colder conditions yielding the highest quality wool. The fibers are remarkably thin, with a diameter of just 12 microns, making them six times finer than a human hair. It takes the wool of one goat to make a single scarf, and three goats to produce enough wool for a shawl. For over 400 years, Nepalese craftsmen have honed their skills, passing traditions down through generations to create these exquisite shawls.

Once a staple of royalty, pashmina and cashmere shawls have become a coveted fashion accessory, with intricately beaded and embroidered designs that showcase the superb workmanship and infinite variety of colors and patterns.

Making of Pashmina Shawl

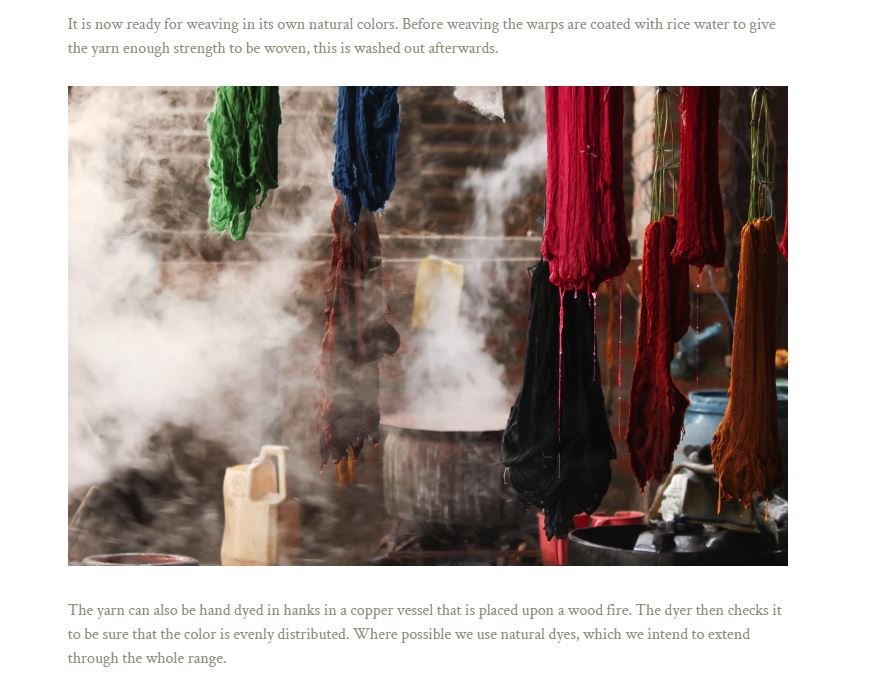

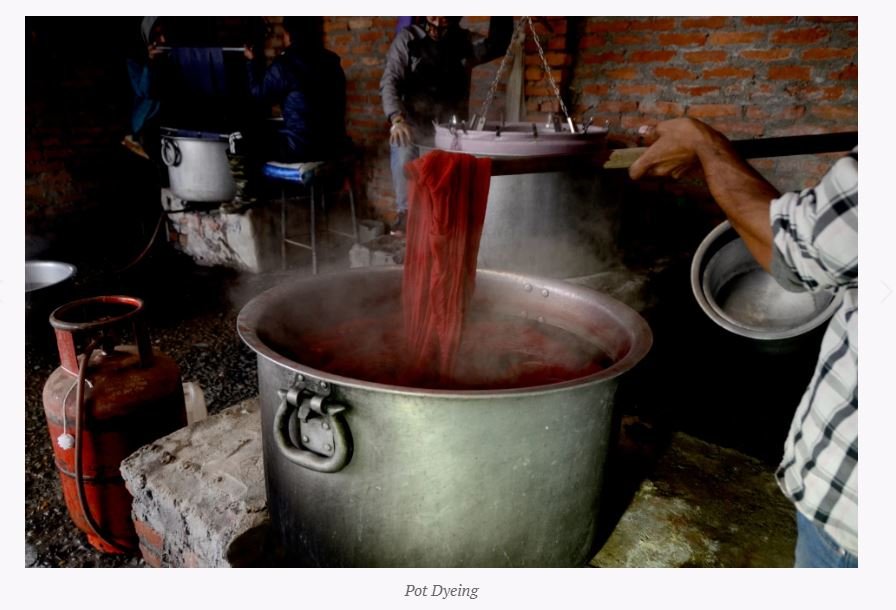

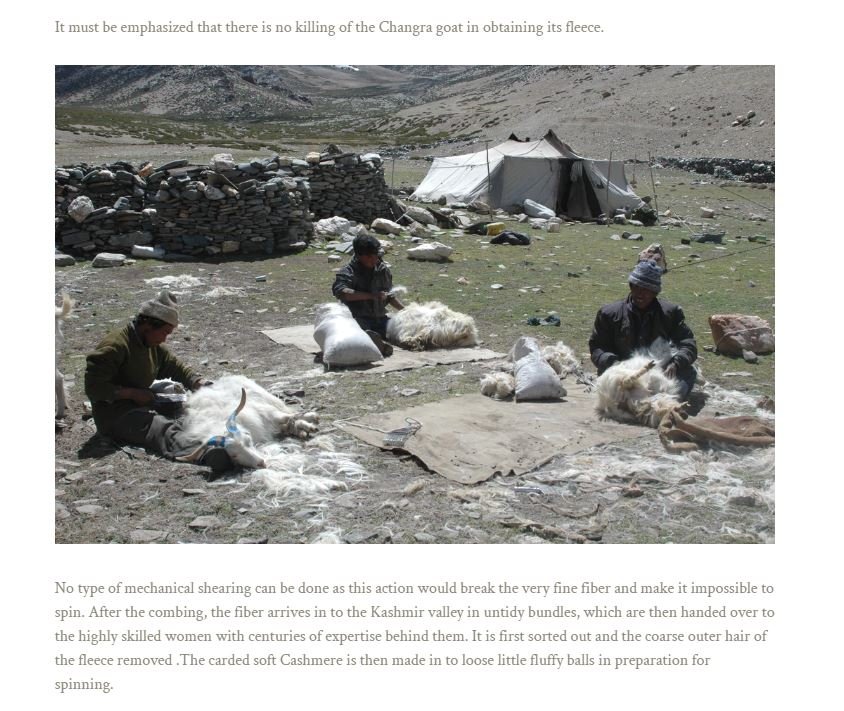

"The art of crafting a Pashmina shawl is a labor-intensive process that spans three weeks, from the initial combing of goats' hair to the final inspection. In the foothills of the Himalayas, flocks are combed by hand to collect the soft, white underbelly hair. This fiber is then separated from coarser hair and sent to cottage industries, where skilled weavers spin and weave it with silk on hand looms. The shawls are then washed with natural soap and entrusted to the dye master, who uses Eco-friendly Azo dyes to create vibrant colors. A two-toned shawl requires hours of careful handling, as the dye master and assistant hold the shawl above the dye pot, allowing the color to seep through. After drying in the sun, the shawls are passed to fringe experts, who craft the tassels. Following another wash and dry, the shawls are ironed and inspected. On the hand loom, silk is woven lengthwise, while Pashmina wool is woven sideways, imparting strength to the shawl. Exceptionally fine Pashmina shawls, known as 'Ring Shawls', can be pulled through a wedding ring."

Disclaimer

Kindly be advised that the images shown on this page are provided strictly and exclusively for non-profit educational purposes ONLY. These images are limited solely to informing the public regarding the process of Pashmina production and shall not be construed, used, or utilized for any other purpose beyond this narrowly defined educational intent.

Detailed process of making Pashmina shawls

Collection of raw material

The first step in the process is collecting raw materials from high-altitude regions of Kashmir and Ladakh. During summer, tribal people from Ladakh, Tibet, and China travel to higher regions, collecting raw wool on a barter system. The raw wool is then handed over to collector-buyers in hilly townships, who sell it to traders in Srinagar. The traders sort the raw material according to grades and shades, fixing prices strand-wise. The material is then sold to petty shopkeepers, known as "Phumb-Wain" (wool retailers), who store their valuable merchandise in small cloth and jute bags. These shopkeepers separate rough bain from soft material, count threads of yarn spun by local ladies, and reward the ladies with money and a fresh supply of raw material for spinning. The ladies also receive payment for their spinning services, minus the cost of the fresh supply. This traditional process is a labor-intensive and essential part of creating Pashmina shawls.

The Spinning Process

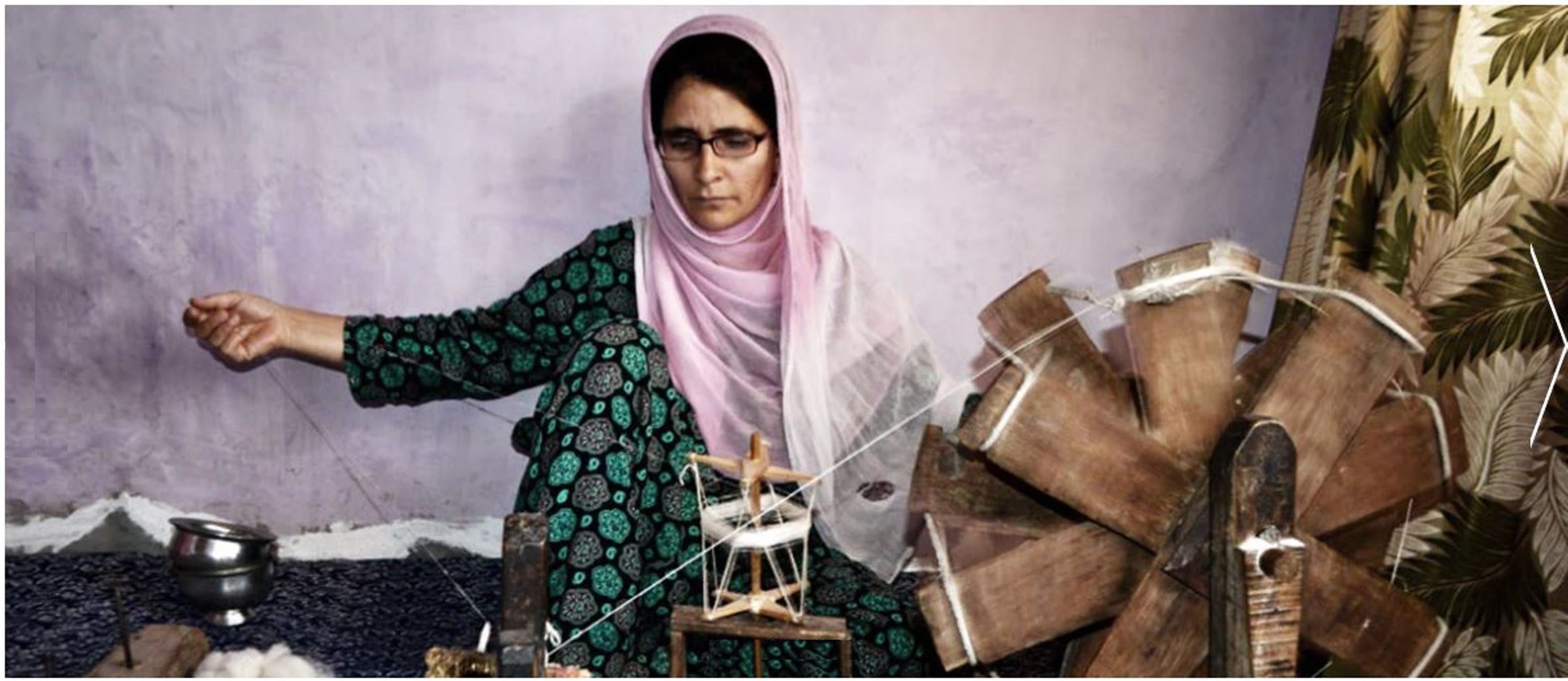

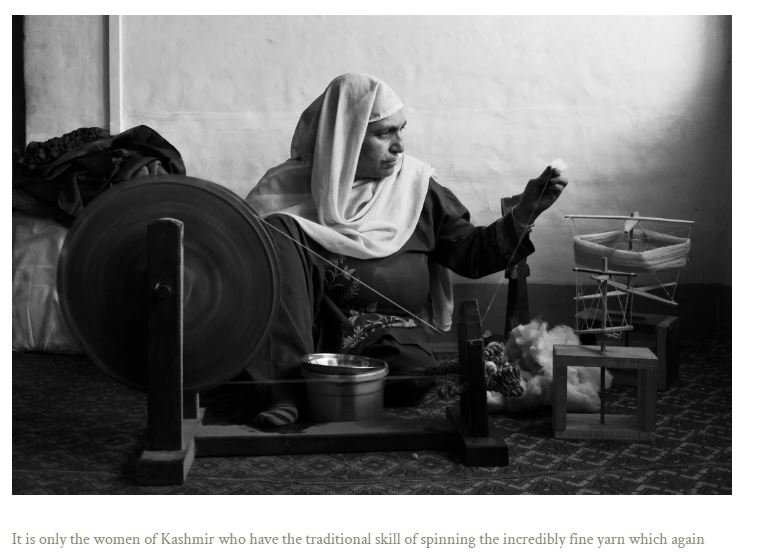

- "The spinning process begins in the homes of local women, who are skilled in this labor-intensive craft. Women over 40 years old are typically engaged in spinning, which requires great effort and patience. The process starts with sifting rough hair from soft material, aided by other family members. The raw wool is then stretched and combed using a 4-wide comb mounted on a wooden stand, a process called "Absawun". Next, the combed wool is mixed with powdered rice in an oval wooden trough, known as Tathal, and left for 3-4 days. This ancient technique whitens and softens the raw wool. After combing the wool again to remove the rice powder, it is formed into large flakes, called Thomb, and placed in round tin boxes. Spinning begins on Saturday, considered an auspicious day, with the eldest lady of the house using a traditional wooden spinning wheel, Yander, to create a soft, delicate yarn. She holds a wool puff in her left hand fingers, supported by her thumb, and spins the yarn as the wheel turns, carefully restoring any cuts that occur during the process. This labor-intensive process yields a small quantity of soft, delicate yarn, a crucial step in creating Pashmina shawls."

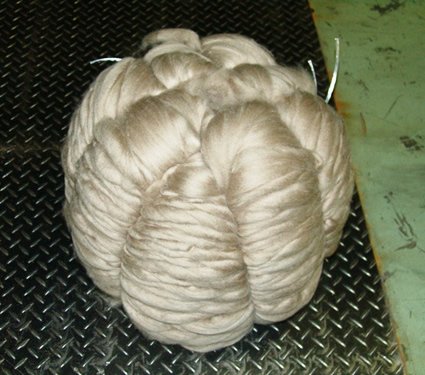

The wool is spun by hand using a traditional spinning wheel to create a fine, lightweight yarn. This process is usually done over a wooden Charkha, also known as a Yinder.

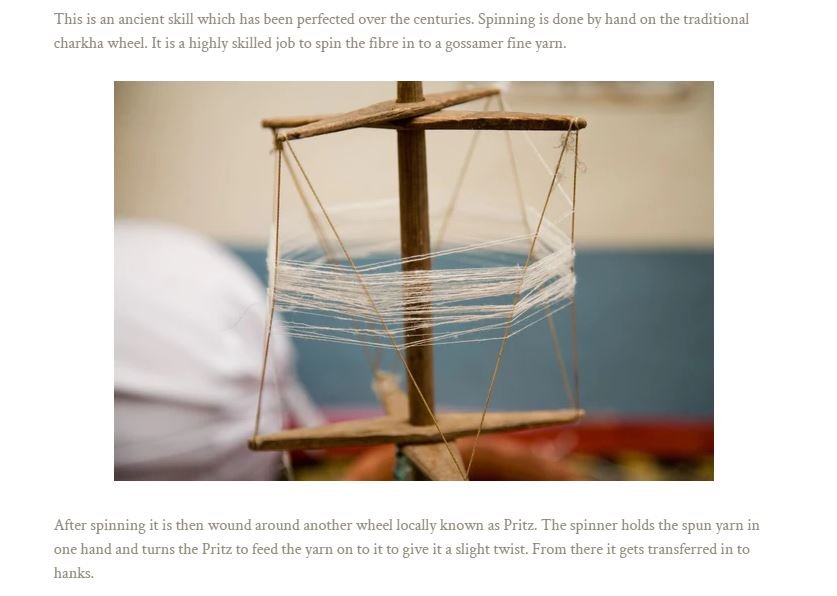

The Pashmina Wool Yarn - "The yarn, mounted on a piece of straw, is called a "Phamb Leeat". Three or four of these straws are placed in an earthen bowl called "Kondul", marking the start of the second phase. The yarn is then turned and twisted on the wheel to make it firm yet fine, and is transferred to a wooden spool called "Prechh". The yarn is then wound onto its edges, known as "Yaeran Doul". The yarn is called "Pun" (thread), and ten rounds of yarn tied together with cotton thread at one or two points (known as "gand") serves as a unit of measurement for payment to the spinner. The finer the yarn, the higher the payment. A bunch of yarn is called "Puyoe" and is typically sold to the same shopkeeper who provided the raw material. At this point, the buying pattern shifts from weighing to counting, with two knots (gand) of yarn, numbering twenty threads, called a "Jora" (two). Unfortunately, unlettered women artisans may be cheated by unscrupulous buyers during the counting process, as payment is made according to the market rate per "Jora". On average, a woman worker can spin ten to fifteen grams of Pashmina per day."

The Weaving Process

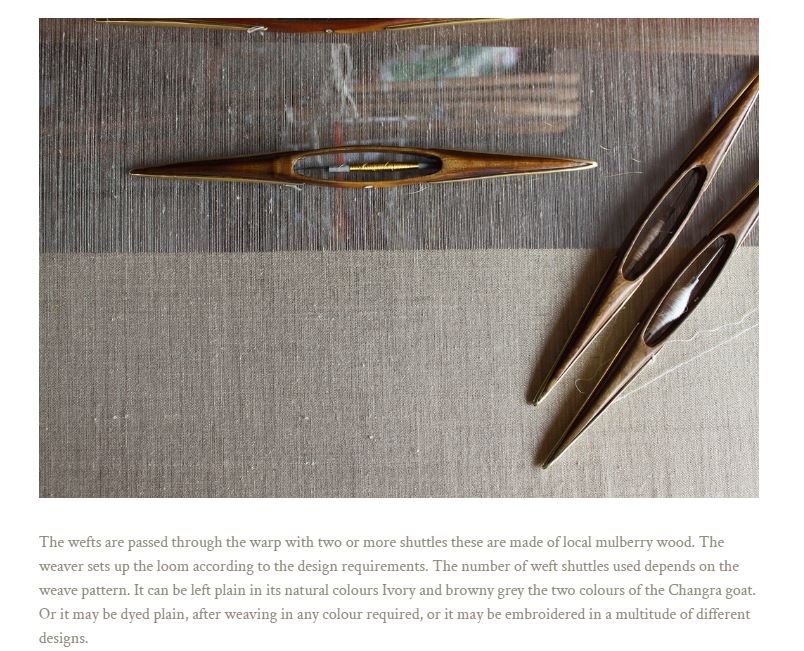

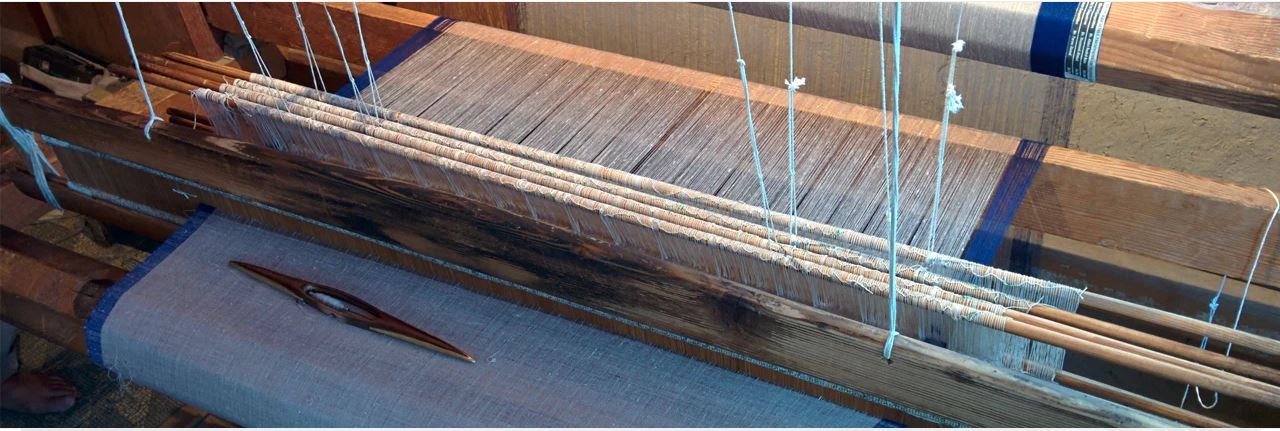

- "The Weaving Process: The shopkeeper (Phamb Wain) sorts and sells the spun yarn to the weaver, who in turn, sorts it by shade and fineness. The spun yarn is used as warp, and the thick yarn as weft. The weaver counts and weighs the yarn, making entries in a register. The yarn is then soaked in a homemade starch made from boiled rice-water (Maya) for a couple of days, before being dried in sunshine. Once dry, the yarn is untied and mounted on a wooden spool (Preeh), a process called Tulun. This is followed by the Yerun process, where the yarn is transferred from the Preeh to iron rods driven into the ground, using smooth sticks. This prepares the wrap for use. About 1200 threads, arranged in this manner, are known as Yaen, sufficient for making four to six shawls. The wrap is brushed, broken threads rejoined (Pen Kem), and carefully mounted on the iron rods, ready for weaving."

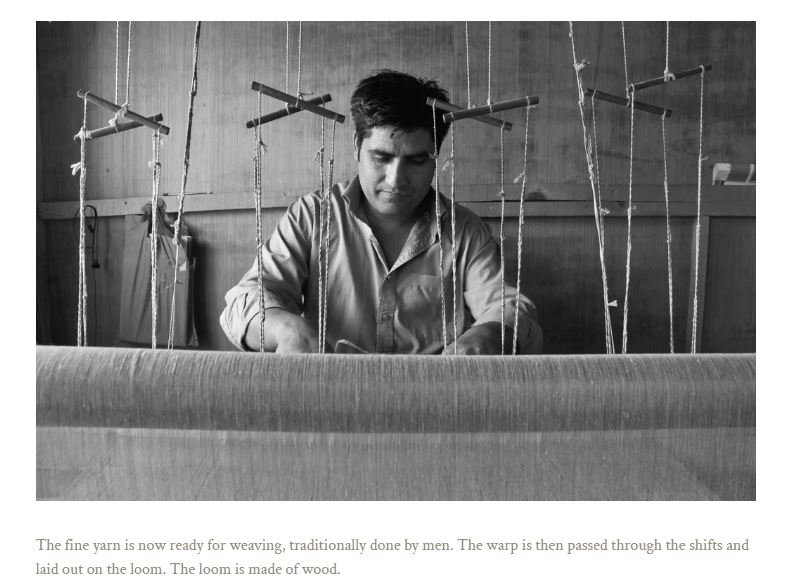

The yarn is dyed and woven into fabric using a traditional handloom. This process is slow and requires great skill. In Kashmir, the process of weaving is called Wonun and is done by an artisan called a Wovur. The warp is made by manually winding the pashmina yarn across 4 to 8 iron rods erected on the ground. It takes about six to eight days to weave a single Pashmina stole or shawl.

Washing of the shawls

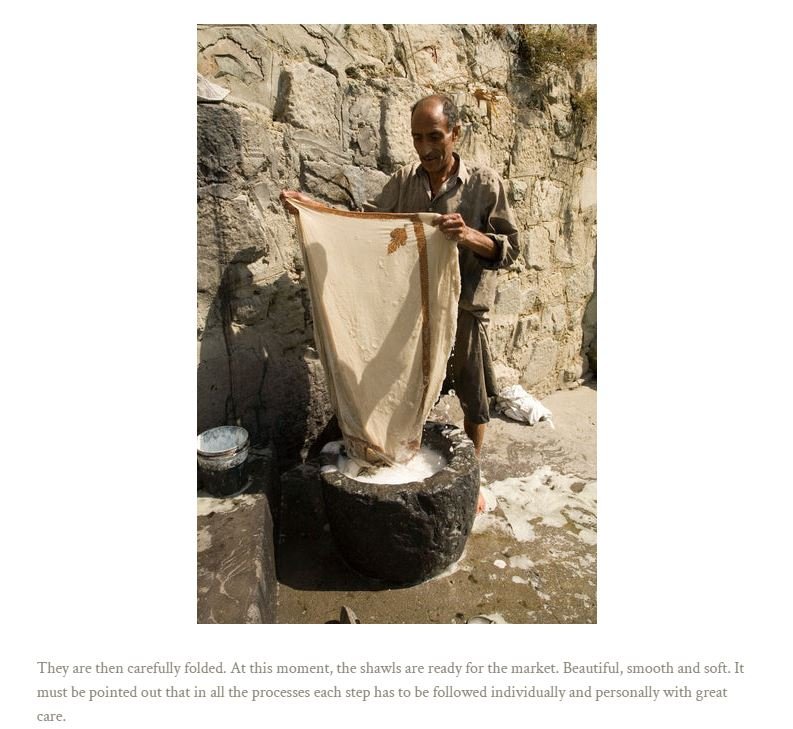

Once the yarn is hand loomed into the shawls, the fabric is washed in running river water to remove the starch.

Dyeing the Pashmina shawls

"The Pashmina shawls are now entrusted to a skilled dyeing master, who meticulously dyes each shawl in large open vats filled with hot boiling water. Eco-friendly Azo dyes are used to achieve the desired hue. This process is both labor-intensive and exacting, requiring the dyer to be highly skilled. It takes many hours to dye and re-dye the shawl to achieve the desired color. The process is especially challenging when creating two-toned shawls, which require careful handling and precise control as the dye master and assistant hold the shawl above the dye pot, allowing the color to gradually seep through."

Drying the shawls

"Following the meticulous dyeing process, the shawls are carefully laid out to dry in the sun-drenched open fields, allowing the gentle warmth to gently settle the colors and soften the fibers."

Fringe making process

- "Next, the shawls are handed over to the skilled fringe experts, who deftly roll the tassels on their legs with remarkable speed and precision, able to expertly finish the fringes on up to eight shawls per day, a testament to their nimbleness and craftsmanship."

Final process of re-dyeing

- "After a final wash and dry, the shawls are meticulously hand-ironed to remove any wrinkles or creases. Each shawl is then subjected to a rigorous inspection, with utmost care and attention to detail, to ensure that every piece meets the highest standards of quality and craftsmanship."

Embellishing the shawl with Hand Embroidery

- "Finally, the Pashmina shawl is entrusted to skilled artisans for exquisite embellishments such as intricate hand embroidery, delicate beading, or lavish sequin work. Each shawl is transformed into a one-of-a-kind masterpiece, boasting exceptional craftsmanship and timeless elegance. Whether adorned with intricate patterns, shimmering beads, or luxurious fringes, Pashmina shawls are a lasting symbol of luxury and a treasured possession for generations to come."

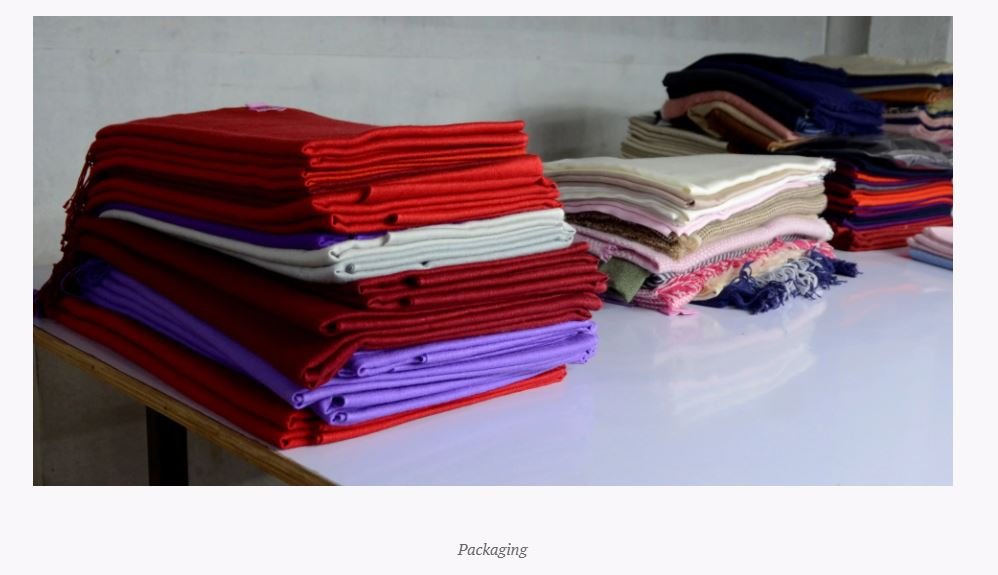

Ironing and Packing the Shawls

After the Pashmina shawls have undergone a rigorous inspection to ensure flawless quality, they are carefully hand-ironed or roller-pressed to remove any wrinkles. Finally, they are meticulously packaged in plastic bags, ready to be presented to discerning customers. With their exceptional craftsmanship, intricate designs, and luxurious softness, these shawls are truly a testament to the skill and dedication of Nepalese artisans. Now, they await their new owners, who will undoubtedly treasure them for years to come

![cashmere.summ[1].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/572bf82f7da24f08f7577a61/1710283948537-5J5IKDIVTLAH2TFUP5YC/cashmere.summ%5B1%5D.jpg)